San Lorenzo de El Escorial

Back in 2013 I had wanted to come to San Lorenzo de El Escorial, just outside of Madrid, but, for whatever reason, we just never managed to do it. I wasn’t about to miss a visit this time around. My time in the capital was quickly approaching the end but I still had enough days left.

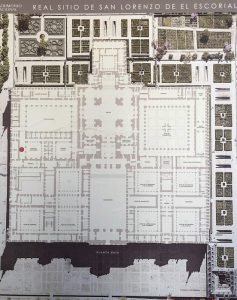

El Escorial is a little town with a very large royal palace and an even larger park. The palace is not just a palace, either; besides containing the XVI century Royal Monastery of San Lorenzo de El Escorial, it also functions as a basilica, pantheon, library, museum, university, school, and a hospital. All in all, there is a lot here but not everything is open to the public, of course.

The royal Escorial consists of two architectural complexes of great historical and cultural significance: the royal monastery itself and La Granjilla de La Fresneda, a royal hunting lodge and monastic retreat about 5 kilometres away. During the XVI and XVII centuries, these two were the places in which the power of the Spanish monarchy and the Roman Catholic church in Spain had their headquarters, so to speak. Interestingly, only Phillip II, the man responsible for their construction actually lived in the main building, the lodge being the preferred sleeping quarters for the others.

When I got off the Renfe Cercanias train, I decided to walk up to the main building along the aptly named Paseo de la Estación. Doing so meant climbing an ever rising hill to where the palace sits nestled next to the old town centre. I picked a rather warm day to do this excursion so I was starting to feel the heat early on. But as the massive façade of El Escorial came into view, I reminded myself that I’d be spending a lot of time inside soon enough.

As I got close to the large parade area in front, however, I was surprised to see a lot of school kids out and about, so of course my first thought was “damn, I’ll be following annoying kids on field trips” all day long, but it turned out that all these kids weren’t going to be my co-visitors–they actually go to school in the building, or some part of it. Did I mention this place was big? What I found fascinating was the fact that these kids were going to school in a place of such history and I wondered if they ever felt any awe at that fact? Do children even think about that? I sure do and I’d like to think I would have thought so in my youth as well, but when you grow up surrounded by so much history, do you even notice it anymore?

A bigger problem I was having at the moment, however, was not finding the main entrance to the tourist-friendly part of the Escorial. There didn’t seem to be a nice, big, and obvious main entrance with a ticket booth and I didn’t want to look stupid and ask one of the kids. I did eventually stumble onto it and got myself inside. The 15€ entrance fee was a little more than what I’ve been paying at other museums but I had come all this way and there was a lot to see, or so I hoped. I didn’t purchase a tour or anything like that but there were very helpful signs and arrows everywhere taking me from point of interest to point of interest quite efficiently.

First up was my favourite, the library. To get to it, I had to go through at least one small courtyard (there are a number of small ones and three large ones), though I’m not quite sure which one it was. Once you pass the first doors, there are so many twists and turns following the designated path causing me to quickly lose my sense of direction. I did end up in the large Patio de Reyes, that leads to the basilica, but I made a left turn in the middle of it to enter the long and narrow Biblioteca de Manuscritos. As soon as I entered my jaw dropped, literally. The main room that is open to visitors is long and narrow with a curved painted ceiling, with massive globes and display cases down the middle, and, of course, bookcases along the walls, nestled between windows. All those internal courtyards allow for many windows in all the spaces, guaranteeing a lot of light inside, even deep inside the structure. This was also the first place I was strongly rebuked for daring to take a picture or two. What’s with that, anyway? What are they afraid of? It’s not like a shake of a finger was going to stop me anyway. All their prohibitions just meant that my photos aren’t as straight as they could be or have the best light, that’s all. I would never leave that library with nothing to remember (visually). It is way too beautiful a space for that to happen. So, once again, you’re welcome but sorry for the small numbers and lack of detail. I do what I can.

My next stop was the basilica, where I did take some pics too, but because I was weary now I didn’t dare take too many. El Escorial may be the largest renaissance building in the world but the church is decidedly gothic and has a rather austere feel to it. The various chapel altars are quite beautiful and large, but the building itself is just a lot of stone. Good thing I like stone. I actually prefer this sort of minimalist decor to some of the super ornate ones I have seen elsewhere.

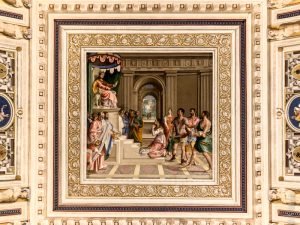

After the basilica, the arrows led me to the Patio de los Evangelistas (Courtyard of the Evangelists), where the courtyard is surrounded by galleries of the main cloister, decorated with frescoes by Pellegrino Tibaldi. In the East gallery, I found a splendid main staircase with a fresco-decorated vaulted ceiling depicting The glory of the Spanish monarchy, painted by Luca Giordano in 1692. I was somewhat unlucky to be crossing paths with a tour group whose leader was rather insistent I don’t take pictures, so I had to be rather careful around her. I did manage to get a few good shots but definitely not as many as I would have liked. The ceiling over this staircase was stunning, and, after the library, my favourite part.

Another set of beautiful rooms is just off the Patio de los Evangelistas: the symmetrical Salas de los Capitulares, which served as meeting spaces for the monks. From there, I made my way to El Panteón de Infantes, built by Isabel II. This is the final resting place of princes, princesses, and consorts other than the parents of monarchs, and covers nine chambers with many, and I mean many, white marble sepulchres, not all of which are filled (just over a half are, as a matter of fact). Some are quite small, making me think at first that this is where they buried the royal children, since so many of them had the habit of dying young. There are quite a few truly small ones, that is true, but adults are buried here too. The place is a little creepy, to be honest, though all that white marble does make a bit less depressing–the lighting inside was rather poor to boot. I got into trouble here too but managed to get a few shots.

Lisa had mentioned the Pantheon of Kings I should definitely see, but, unfortunately for me, it was closed to visitors. El Panteón de Reyes is where the actual kings and queens are interned, though only Isabela II was a queen regnant. The other queen consorts had to have been mothers of kings to be allowed in here. Not being able to see this very special place just means I’ll need to go back again one day, something I will definitely not say ‘no’ to.

After being down below ground, it was time to see some of the upper rooms, starting with the Palacio de los Austrias, Philip II’s bedrooms and other royal spaces. I only managed to get a photo of a couple of rooms here, la Galería Real and la Sala de Batallas. The king’s bedroom was rather austere but it did have a special window to the basilica so he could attend mass when laid up by gout. He also had amazing views looking out to the countryside and I did get many pictures of those. I also peeked in to see the queen’s bedroom which was tucked away in behind. I again wondered about the location of these rooms and the function of many of the surrounding ones, but, ultimately, I am left to wonder forever, because what we are allowed to see these days doesn’t ever seem to make sense since we only see a fraction of the spaces actually there. One day I’d like to get a private tour behind the scenes just to assuage my curiosity but I will not hold my breath. I just don’t have friends in the right places for that.

Slightly frustrated, I continued on to the Bourbon part of the palace, or, I should say, the Palacio de los Borbones, the XVII century dynasty who continued to come to Escorial every year to spend autumn there. Carlos III updated the decor in the current style (French) and you can definitely see the difference: the spaces are much more colourful and luxurious. Again, the views were amazing from up here.

Finished with the interiors, I decided I needed to check out the gardens. What I didn’t realize was that I had to go all the way around to the back of this massive building in order to do so. After a couple of hours of wandering inside, I now had to do the same outside, but this time in the middle of the hottest time of the day. Once again I had to make my way through throngs of children out for their midday play time on the stone plaza in front, all the while making sure not to trip on the uneven stones. Which begs the question: how do the kids not fall down all the time because tripping on those bits that stick out must be a certainty. To their credit, I never saw anyone fall though I did have to be quite careful myself.

The gardens were not as exciting as I had hoped, but I did do a thorough examination of them: the wall of roses was quite stunning, the large pond with the one swan was quite cool, and the yelling peacocks hardly visible but I did find them. The racket they were making made it easy to do. Unfortunately for me, the only way back to the front of El Escorial was to retrace my steps to the garden entrance I used earlier, and then back through the kids’ play zone. I was hungry and tired and grumpy by then, but there were still many hills/stairs to climb since the commercial are of the town of El Escorial sits above the palace itself. I couldn’t decide where to eat but eventually found a little Italian place where I had a very good pizza.

I had some time left before taking the train back, so I took the long way and sauntered through Parque y Jardines de la Casita del Príncipe, a large park with wide avenues, with a very gentle slope down to the station. The Prince’s Cottage was for the private use of the heir to the Spanish throne Charles, Prince of Asturias, and his wife Maria Luisa and it was constructed in the 1770s. It doesn’t have any bedrooms, however, as the prince and family slept in the main house but the cottage was used to hide away from the hustle and bustle of the palace; you can say it was the ultimate backyard “shed.” Unfortunately–and I am getting tired of saying this–it wasn’t open to visitors either.

All in all, my visit to El Escorial was a success, and I look forward to returning here again one day. As I learn more about the various kings and queens, many of these places take on a different meaning, one of familiarity and relevance. For now, their names and years of rule all blend in but I will get them straight one day, something that should make visits to El Escorial much more meaningful.